Defeat the Game Master

By Jordan Moles on October 2, 2023.

In the heart of a dimly lit tavern, lost somewhere in a strange multiverse of Dungeons and Dragons, a group of individuals as diverse as they were noisy gathered. Thunderous laughter echoed through the smoky establishment as dice of all shapes whirled through the air, coming to rest with a satisfying clatter to determine the fate of their owners. Seated on rickety stools around an old, weathered wooden table, our heroes, or at least what one could call them, were gearing up for a well-deserved evening of beer, dice, and camaraderie.

Let's Make Introductions!

At the center of this eclectic gathering, the Ranger stood, self-proclaimed leader of the team.

His main mission was to maintain peace within the group, especially between the Elf and the Dwarf, two individuals known for their disagreements.

However, despite his efforts, he was often overwhelmed by despair, especially when things went awry. The Ranger wasn’t specialized in any particular skill but rather versatile.

He had the unfortunate habit of overestimating his abilities and attempting to use talents he didn’t quite master.

To his left, the Barbarian held his place.

He was a colossal figure with bulging muscles, wielding a sword as an extension of his mighty arm. The Barbarian’s life boiled down to two passions: combat and carousing with the Dwarf.

He held no fondness for magic, which he saw as a weakness. He was often quick to judge the other group members as weaklings or cowards if they didn’t share his fervor for melee.

On the other side of the table, the Elf lounged with natural grace. With her enchanting beauty, she appeared to be free from all worries. Her carefree and lighthearted demeanor stood in stark contrast to her companions.

Her behavior was often seen as eccentric, although she seemed unaware of it.

She maintained a tumultuous relationship with the Dwarf, their mutual antipathy having become legendary among the tavern’s regulars.

Next to the Barbarian, the Dwarf, a robust and choleric warrior, prepared to enter the arena of the impending game. His primary obsession was money, and he was willing to do anything to fill his purse, even embarking on perilous adventures with companions he couldn’t stand, especially the Elf, with whom he had an abominable relationship.

The Dwarf was also an expert in complex calculations, particularly when it came to distributing loot among the group members, taking into account various criteria such as time spent together, the danger of situations, and the experience gained in battles.

He never missed an opportunity to savor good hams and brandish his small axe, which he wielded with great skill.

In the shadows, the Rogue, dressed discreetly, observed the scene. His sharp eyes scanned for the next purse to steal.

His legendary agility and dexterity made him a master in the art of theft, but it also meant that he couldn’t resist pilfering small things, even among his companions.

His dark demeanor and black leather tunic left little trace as he slipped into the shadows. His lock-picking, thieving, and espionage tools were carefully concealed under a discreet belt.

Next to the Elf, the Magician sat. She was a woman with deep red hair, passionate about all sorts of literature, with a particular fascination for spellbooks.

Unfortunately, her magical talents were limited, and she didn’t particularly shine in that area. Despite her lack of magical aptitude, she made up for it with her in-depth knowledge of books.

In terms of attire, she typically wore a long dark blue robe adorned with silver motifs that resembled sparkling stars. Her outfit was complemented by a matching pointed hat, adding a touch of mystery to her appearance. She also wore a leather belt with pockets for storing small magical items and components for her spells.

The Magician remained an invaluable source of knowledge for the group and played a central role within the company, effectively sharing leadership with the Ranger.

Finally, by their side stood the Ogre, an imposing creature. His insatiable appetite manifested in primitive grunts. Although he was of a kind nature, he remained a constant source of trouble, overturning chairs and breaking glasses at regular intervals.

His actions were primarily dictated by instincts, which made him akin to the Barbarian, with whom he shared a passion for good food. However, he had a special connection with the Magician, the only one capable of understanding his language.

The Rules of the Game

After several pints of beer, heated arguments, questionable jokes, and epic anecdotes, the atmosphere in the tavern was at its peak. The loud laughter and off-key singing of the adventurers filled the room, while the overwhelmed waitresses tried to fulfill the ever-increasing orders.

The Magician, fueled by the festive ambiance, decided that the moment had come to add an extra touch of excitement to the evening. She suddenly pulled out a set of 14 mysterious dice from her bag, 2 each, immediately grabbing the attention of her companions. Curious looks fell upon the dice as conversations gradually quieted.

With a mischievous smile lighting up her face, she announced in a clear voice, “My friends, we’re going to spice up this evening with a dice game! Who’s ready to try their luck?”

The Magician’s announcement sparked a wave of enthusiasm among the already tipsy adventurers.

The Dwarf, always eager for opportunities to gain gold but unwilling to wager his own, slammed the table with his calloused hands and exclaimed, “By the beards of our ancestors, I’m in!”

The Elf, despite her frequent disagreements with the Dwarf, smiled and said, “Why not? It could be fun.”

Even the Ogre, whose limited facial expression didn’t reveal much, emitted a consenting grunt.

The Ranger, followed by the Barbarian and the Rogue, quickly went to fetch some supplies, a cheese board, and some country ham before attentively listening to the rules of the game.

The Magician, delighted to see that her idea had been so well-received, rummaged through her bag and pulled out a large parchment. It contained the fundamental laws that had to be read before playing. They were written in a peculiar manner, resembling runes that only the Magician could decipher, but here is the note magically transcribed into our language:

Dear mortal, beware, for I shall initiate you into the profound mysteries that govern these sacred dice. They are subject to enigmatic laws that you must understand before unleashing them on the table. Follow my words carefully, and you shall discover the hidden power behind each roll. Here is the most important one, the one that defines them all.

Let (\(\Omega\), A) be a measurable space, where \(\Omega\) is the universe and A is a sigma-algebra. A probability measure is a measure with a total mass of 1, and it satisfies the following three axioms:

• For any set E in A, the probability \(\mathbb{P}\)(E) is a real number between 0 and 1.

• The probability of the universe \(\Omega\) is equal to 1, meaning \(\mathbb{P}(\Omega) = 1\).

• Probability is \(\sigma\)-additive, which means that for any finite or countable family of pairwise disjoint sets \((E_i, i \in I)\) in A, the probability of their union is equal to the sum of the individual probabilities:

\begin{equation*}\mathbb{P}\left(\bigcup_{i\in I} E_i\right) = \sum_{i\in I} \mathbb{P}(E_i)\end{equation*}

In particular, the probability of the empty set (\(\emptyset\)) s equal to 0, i.e., \(\mathbb{P}(\emptyset) = 0\).

The Elf, the Barbarian, and the Ranger scratch their heads in confusion, while the Dwarf, always attentive to the prospect of winning gold, silently nods. The Magician, seeing that her explanations haven’t been understood by everyone, decides to simplify further.

She takes a small piece of paper from her pocket and begins to explain more concisely: “Alright, let’s forget about the complicated terms. The universe is simply all possible outcomes. For example, when we roll a die, the possible outcomes are 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6. That’s the universe, which we denote as \(\Omega=\{1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6\}\).

Then, a sigma-algebra is the set of all subsets of the universe, meaning all possible groups of results we can obtain. For example, a subset could be the set of even numbers, which is \(\{2, 4, 6\}\).

Do you follow so far?

Let’s move on to the axioms. The first one is simple: it just says that the probability of an event is always between 0 and 1. In other words, this means that the probability of getting a result is always either zero (impossible) or one (certain).

The second axiom is even simpler. It says that the total probability of all possible outcomes is always 1. So if we add up the probability of getting each number on our die, it must always equal 1.

The third axiom, a bit more complex, means that if we have two events that cannot happen at the same time (disjoint), then the probability of either one happening is simply the sum of the probabilities of each. For example, the probability of getting a 1 or a 6 when rolling a fair die is the sum of the probability of getting a 1 and the probability of getting a 6.

I hope this clarifies things a bit!”

The Magician, aware that her companions are starting to get impatient with the technical terms, decides to simplify the explanations further to make the concepts more accessible.

She continues her narrative: “Now, let’s forget about the complex terms for a moment. The laws of probability can be described in three major categories of characteristics, as indicated on this parchment:”

•«There are position parameters that influence the central tendency of the probability distribution. They determine the values around which the probability is most concentrated, which means where most of the results cluster. Among these parameters, we have the expectation, which is a measure of the average, the median, which is the central value, and the mode, which is the most frequent value.”

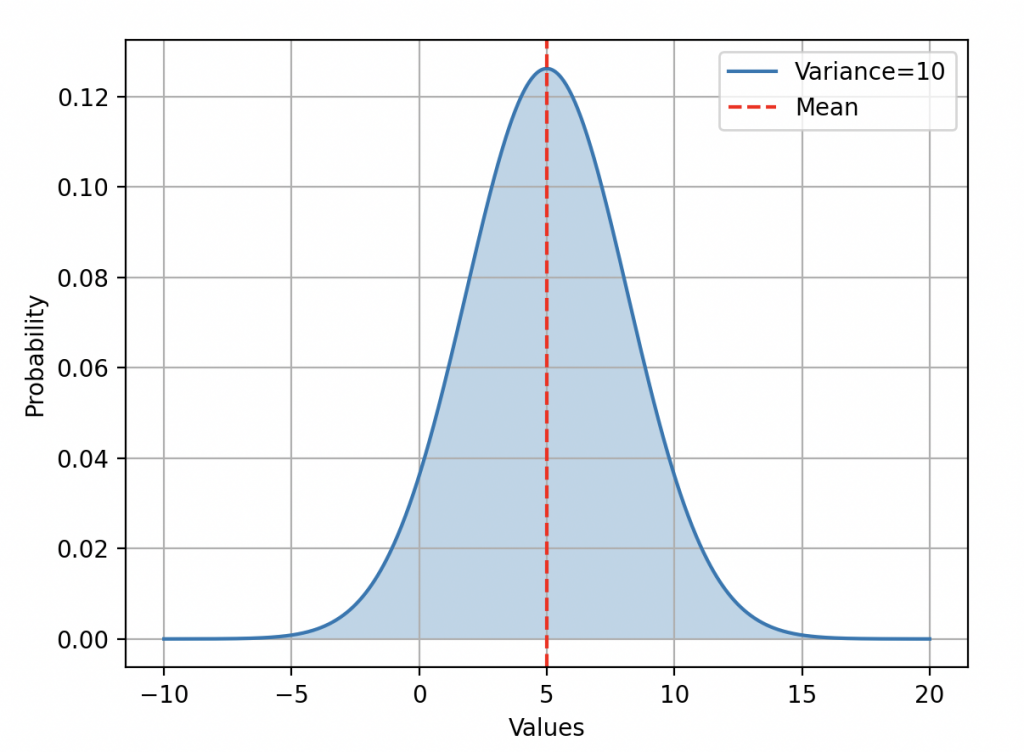

Normal distribution with a mean of 5 and a variance of 10.

• “Then there are scale parameters, which measure how spread out or tight values are around those central values. Variance, standard deviation, and interquartile range are examples of these parameters. We often focus on variance, which works like this:

If it’s close to zero, it suggests that individual values are similar and cluster closely around the mean.

Conversely, high variance indicates that individual values are farther from the mean, with a greater overall spread.”

Two normal distribution laws with a mean equal to 5 and a variance equal to 2, and the other one with a mean equal to 20.

• “Finally, we have the shape parameters. They describe how probabilities change as we move away from the central values.

For example, skewness measures if the distribution is tilted to one side or the other, and kurtosis, or the coefficient of kurtosis, examines how closely values are concentrated near the mean.“

Normal distribution with zero skewness and a normal distribution with skewness equal to 10.

The Law of the Die

The Magician paused before concluding: “Now that we’ve gone over these concepts, let’s dive into the heart of the matter that seems to interest you: the discrete uniform probability distribution.”

The Elf: (whispering to the Barbarian) Oh, it’s about time; it’s almost bedtime.

The Barbarian: (chuckling) Yeah, I hope this magisterial lecture ends before midnight.

The Ranger: (smiling) Maybe we should prepare some blankets for our tired comrades.

The Magician, looking at them with an amused expression, decides to continue despite her companions’ teasing remarks.

The Magician: The discrete uniform distribution is perhaps the most important probability distribution you need to understand here. It ensures equiprobability, meaning that each outcome has an equal probability for each mode in a finite set of possible modes.

The Dwarf loses patience with all the jargon and snatches the parchment from the Magician’s hands.

The Dwarf: (furrowing his brows) Hold on… does this old parchment say I should give you a gold piece? I’m not sure why I should do that.

The Barbarian: (laughing) Haha! The parchment predicts the future! Come on, Dwarf, give her the coin!

The Dwarf refuses to give up his coin, but the impatient Barbarian punches him in the head.

The Barbarian: (laughing) Come on, Dwarf, do it for education! It only costs a coin.

The Ogre: (banging the table and laughing heartily), Zog zog.

The Elf: Well done.

The Dwarf, slightly dazed from the blow, reluctantly hands over a gold piece to the Magician along with the parchment.

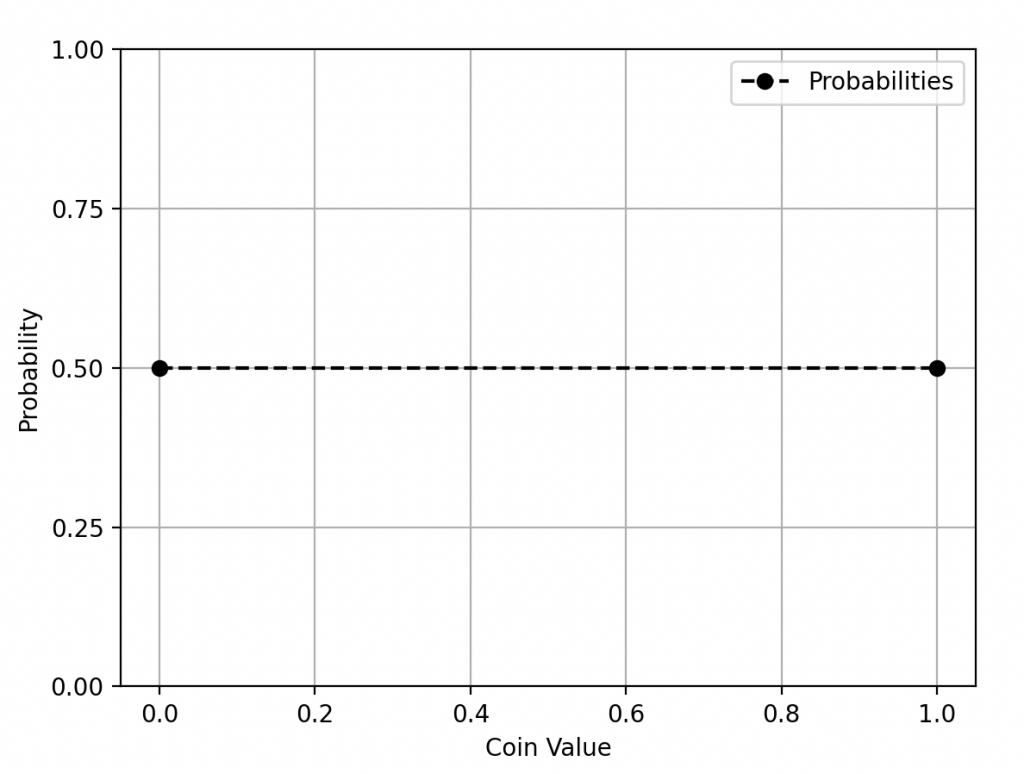

The Magician: Perfect, thanks for your contribution. So, to better understand, imagine a fair coin. When you toss it, each side has an equal chance of appearing, which is 1/2.

Discrete uniform distribution with two outcomes (Coin toss).

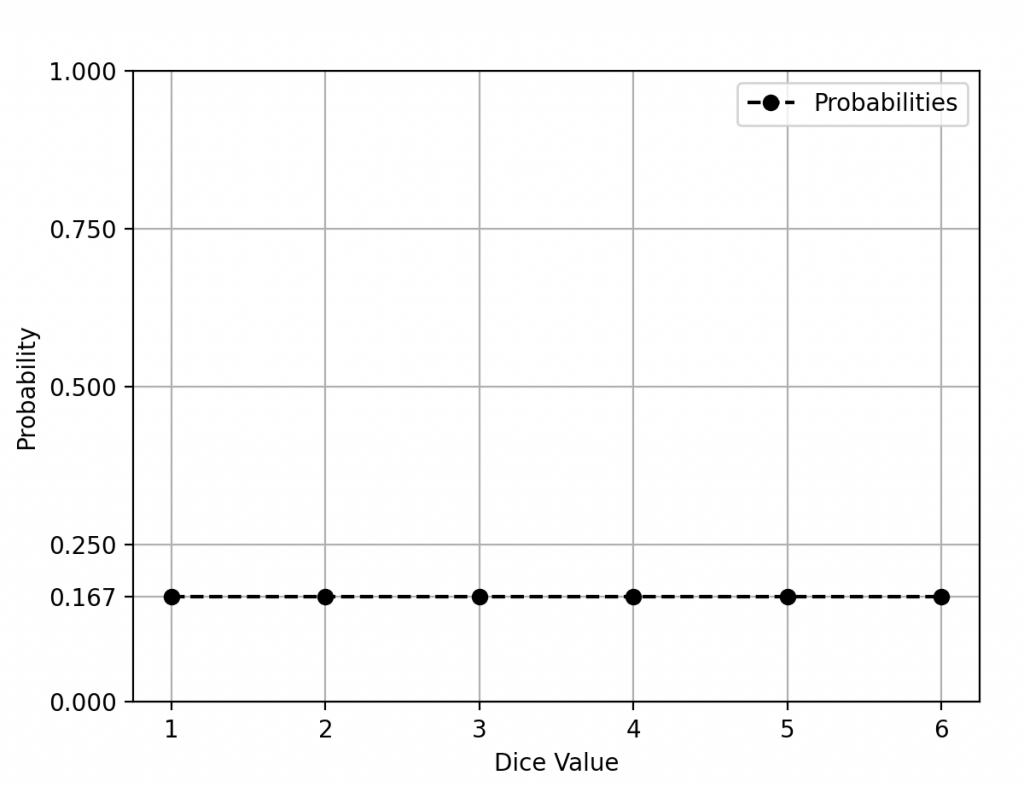

For my dice, it’s the same thing. A standard die has 6 faces, which corresponds to 6 modes, and if it’s balanced, we say they are all equiprobable.

Discrete uniform distribution with six outcomes (Roll of a die).

The Thief: (curiously) Show me that coin, I’d like to examine it closely to better understand the heads or tails.

The Magician: (handing the coin to him) Of course, here’s the coin. It’s balanced, so each side has an equal chance of landing.

The Elf: (raising a hand) Wait, what can we say about the die, too?

The Magician: (smiling) Many things. Here are the main characteristics of these dice:

We call \(X\) the random variable that follows the discrete uniform distribution (the roll of a die).

• The expectation: it’s like the average, and for a standard die, it’s \(\mathbb{E}(X)= \frac{6+1}{2}=3,5\)

• The median: it’s the middle value, also \(m(X)= \frac{6+1}{2}=3,5\) for a fair die.

• The mode: there isn’t one here because each face has the same probability of appearing.

• The variance: it measures the spread of results, and for a fair die, it’s approximately \(V(X)=\frac{6^{2}-1}{12}\approx2.91\)

• The skewness is zero, and the kurtosis…

The Ranger: (interrupting) Excuse me, but isn’t that enough of the rules? We’ve got the basics.

The Magician: Well, there are a few more laws in this parchment, the triangular probability distribution, the…

The Dwarf: (grumpy) By the beards of our ancestors, we didn’t come here for a math class! We want to roll those dice and play, not listen to endless speeches.

The Barbarian: (slapping the table) He’s right! This is all well and good, but we want action, not numbers!

The Thief: (examining the coin closely) Yeah, I’m with them. Can we start playing now?

The Dwarf: Give me back my coin!

The Magician: (trying to keep her calm) Alright, alright, I see you’re all very impatient. But before rolling the dice, let me just take one last look at this note at the bottom of the page. I want to make sure we’re following all the rules.

The Magician begins to quickly read the note at the bottom of the page, but suddenly stops.

The Magician: (surprised) Wait, there’s something important here that I hadn’t noticed! It says, “Do not flip the coin before playing with the dice because…”

Before she can finish her sentence, the Voleur tosses the gold coin in the air to return it to the Nain. But instead of landing in his hand, the coin starts spinning in the air in a mysterious way, emitting a magical glow.

The Dwarf: (surprised) By the beards of our ancestors, what’s happening?

The coin continues to spin in the air, faster and faster, and suddenly it disappears completely, leaving everyone puzzled.

The Elf: (astonished) Where did the coin go?

The Magician: (shocked) I… I don’t know. It seems like the dice are more mysterious than I thought.

The Barbarian: (excited) Whatever it is, it looks fun! Let us roll the dice now!

The Dwarf: (annoyed) Where is my coin?

It was a night of revelry, heated arguments, and rowdiness in the old tavern. The adventurers had stopped to relax after a long day of exploration, and, as was their custom, they had gotten caught up in the excitement of the evening.

The Dwarf, already in a bad mood, decided that everything was always the fault of the Elf. He had taken the Elf as a scapegoat, attributing all the group’s woes to her, constantly repeating that “it was the Elf’s fault that everything was going wrong.” This deplorable attitude only worsened as the evening progressed.

While they played dice and bet money, the Voleur decided to spice up the evening by discreetly stealing a waitress’s panties. It was an act as audacious as it was risky, but he managed to accomplish this feat with remarkable dexterity.

The Barbarian, on the other hand, gave in to his impulsiveness by punching the bouncer at the tavern’s entrance after a minor argument. The bouncer wasted no time calling for reinforcements, which quickly subdued the Barbarian with a good beating. This plunged the group into an even more complicated situation.

The Ogre, always hungry and curious, decided to satisfy his appetite by swallowing a billiard ball. This caused a great deal of laughter among the tavern’s customers, but also a lot of concern about the Ogre’s well-being.

Finally, the Nain, completely drunk, ended up vomiting his beer on the innkeeper, triggering a general brawl between the adventurers and the other customers.

The ensuing chaos could only lead to one inevitable conclusion: all the adventurers eventually found themselves in the dungeon, where they would have to face new adventures to escape from this predicament. It was the beginning of an adventure that would take them much further than they could have imagined on that night of debauchery and disorder.

The Dungeon

The Ranger, known for his wisdom (or so he claimed), gathered the motley group of adventurers in a dim corner of their filthy cell. The faint flicker of a wavering torch added a picturesque ambiance to their already unsavory situation.

“Listen to me, comrades,” the Ranger began with a firm, though somewhat nervous voice. “We are in a dire situation, but we are not just anybody. We are an elite troupe, and we cannot resign ourselves to being locked up here like common rats in a sewer. What we need is a plan.”

Upon this, the Elf and the Dwarf started bickering like children, calling each other “lichen suckers” and “rock-eaters.” The Dwarf, having thicker skin than the Elf (literally), retorted by insulting the elf’s pointed ears and suggesting that he go back to playing his flute in the forest.

The Barbarian, who seemed incredibly bored, interrupted the quarrel and decided to use his Herculean strength to try and break down the door. Unfortunately, he had taken a severe blow to the head during the arrest and was still groggy from the impact.

The Game Master asked him to make his disadvantage roll, which meant he would roll the die twice and keep the less favorable result. Moreover, the door was made of steel, designed to withstand the efforts of prisoners trying to escape their sentences.

Sélect:

Number of dice = 1

Type of dice = 6

Roll the dice twice and choose the smaller result.

Number of dice

Type of die:

Modifier

Result:

What result do you get ?

Bibliography

P. Barbé et M. Ledoux, Probabilité, Les Ulis, EDP Sciences, 2007.

P. Bogaert, Probabilités pour scientifiques et ingénieurs : Introduction au calcul des probabilités, Paris, Éditions De Boeck, 2006.

M. Lejeune, Statistique : la théorie et ses applications, Springer Science et Business Media, 2004.

F. Caravenna, P. Dai Pra et Q. Berger, Introduction aux probabilités : Modèles et applications : mathématiques, physique, informatique, sciences de l’ingénieur, biologie, Dunod, 1er septembre 2021.

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from scipy.stats import norm

# Parameters for normal distributions

mean = 5 # Common mean for both distributions

variance1 = 10 # Variance for the first example

variance2 = 20 # Variance for the second example

# Generate data for the two distributions

x = np.linspace(-10, 20, 1000)

pdf1 = norm.pdf(x, loc=mean, scale=np.sqrt(variance1))

pdf2 = norm.pdf(x, loc=mean, scale=np.sqrt(variance2))

# Plot probability density functions with transparent fill color

plt.plot(x, pdf1, label=f'Variance={variance1}')

plt.fill_between(x, pdf1, alpha=0.3)

#plt.plot(x, pdf2, label=f'Variance={variance2}')

#plt.fill_between(x, pdf2, alpha=0.3)

# Calculate the mean for both cases (they should be equal)

mean1 = mean

mean2 = mean

# Draw vertical lines for the means

plt.axvline(x=mean1, color='r', linestyle='--', label=f'Mean')

plt.xlabel('Values')

plt.ylabel('Probability')

plt.legend()

plt.grid(True)

plt.show()

print(f"Mean (Var={variance1}): {mean1:.2f}")

print(f"Mean (Var={variance2}): {mean2:.2f}")

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from scipy.stats import norm

# Parameters for normal distributions

mean = 5 # Common mean for both distributions

variance1 = 10 # Variance for the first example

variance2 = 20 # Variance for the second example

# Generate data for the two distributions

x = np.linspace(-10, 20, 1000)

pdf1 = norm.pdf(x, loc=mean, scale=np.sqrt(variance1))

pdf2 = norm.pdf(x, loc=mean, scale=np.sqrt(variance2))

# Plot probability density functions with transparent fill color

plt.plot(x, pdf1, label=f'Variance={variance1}')

plt.fill_between(x, pdf1, alpha=0.3)

plt.plot(x, pdf2, label=f'Variance={variance2}')

plt.fill_between(x, pdf2, alpha=0.3)

# Calculate the mean for both cases (they should be equal)

mean1 = mean

mean2 = mean

# Draw vertical lines for the means

plt.axvline(x=mean1, color='r', linestyle='--', label=f'Mean')

plt.xlabel('Values')

plt.ylabel('Probability')

plt.legend()

plt.grid(True)

plt.show()

print(f"Mean (Var={variance1}): {mean1:.2f}")

print(f"Mean (Var={variance2}): {mean2:.2f}")

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from scipy.stats import skewnorm

# Parameters for the normal distribution

mean1 = 5

std_dev1 = 2

skewness1 = 0

# Parameters for the asymmetric normal distribution

mean2 = 5

std_dev2 = 2

skewness2 = 10 # Positive skewness (right-skewed)

# Create a range of x values

x = np.linspace(0, 10, 1000)

# Calculate the probability density functions (PDFs) for both distributions

pdf1 = skewnorm.pdf(x, skewness1, loc=mean1, scale=std_dev1)

pdf2 = skewnorm.pdf(x, skewness2, loc=mean2, scale=std_dev2)

# Plot the PDFs as curves

plt.plot(x, pdf1, label=f'Skewness={skewness1}')

plt.fill_between(x, pdf1, alpha=0.3)

plt.plot(x, pdf2, label=f'Skewness={skewness2}')

plt.fill_between(x, pdf2, alpha=0.3)

plt.xlabel('Values')

plt.ylabel('Probability')

plt.legend()

plt.grid(True)

plt.show()

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Define possible values (coin faces)

values = [0, 1]

# Calculate uniform probabilities (each face has a 1/2 probability)

probabilities = [1/2] * 2

# Set the values to display on the y-axis

plt.yticks([0, 0.25, 1/2, 0.75, 1])

# Create the scatter plot

plt.plot(values, probabilities, marker='o', color='black', label='Probabilities', ls='--')

# Limit the y-axis scale from 0 to 1

plt.ylim(0, 1)

# Label the axes and add a title

plt.xlabel('Coin Value')

plt.ylabel('Probability')

# Display the plot

plt.grid(True)

plt.legend(loc='upper right')

plt.show()

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Define possible values (dice faces)

values = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6]

# Calculate uniform probabilities (each face has a 1/6 probability)

probabilities = [1/6] * 6

# Create the scatter plot

plt.plot(values, probabilities, marker='o', color='black', label='Probabilities', ls='--')

# Set the values to display on the y-axis

plt.yticks([0, 1/6, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1])

# Label the axes and add a title

plt.xlabel('Dice Value')

plt.ylabel('Probability')

# Display the plot

plt.grid(True)

plt.legend(loc='upper right')

plt.show()